I was working two jobs in London in 1973, one for the rent and the other for the bills, when I saw a Granada TV documentary, The Unlucky Australians. Frank Hardy, a Communist Party member, had written the book on which it was based. I worked three nights a week in a south London pub. The men I pulled beer for worked at the local meat works. They had also watched the program and talked at the bar about what they had seen: people, whose land originally had been occupied by the British government, were slaves for rations at Wave Hill cattle station in the Northern Territory of Australia. They were working for lord Vestey, a British aristocrat who ran cattle on their land.

I say “British aristocrat”, but he got his title because of money and business dealings, not his DNA. Vestey started out with a butcher shop in Liverpool. It was a family business that had expanded dramatically. Not only was it now a chain of shops throughout Britain (Dewhurst), but it had gone global. He owned stations and cattle all over the world – Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela, Guatemala, Australia. He owned the slaughterhouses, the big freezers, the ships carrying the meat and the meat works wherever the produce was loaded and unloaded. And he owned the meat works in London.

So the men in the pub had the same boss as the men and women in the film. The documentary told the story of a strike that started in 1966. They’d walked out for pay, then equal pay. And the strikers were holding out, seven years later, in a strike camp occupying one square mile of what was, according to the paper law, lord Vestey’s land. He paid rent to the government – 55 cents a year for one square mile on one part, 5 cents for one square mile for one year for the rest of it. An agreement let him do that for 99 years. I think Vestey occupied land in the area covering more than 13,000 square miles at that time, roughly the size of Belgium.

The demand of the station workers now was for the return of the land and their right to control it. That night, the men in the pub, 12,000 miles away, decided to call a one-day strike in solidarity. Every worker gave a day’s wages and sent the money to the workers in Australia to support them in their fight.

Why do I tell that story? Because sometimes the big picture comes easy. People, kept down and exploited, making money for the boss – the same boss – saw that big picture: 12,000 miles? Nothing! Different language? Nothing! Different colour? Nothing! No such thing as race. And the same boss! They’re hurting Vestey! Let’s give them a hand! Solidarity, strength, united we stand, revolution around the next corner. Sounds easy! But how easy was it – or should I say, is it? We stood and raised our glasses to the – the who? – the Gurindji? “To the Gurindji!”

Moving south

I had no idea that, not long after, I would end up in Australia. I hadn’t particularly wanted to come. Wasn’t it like South Africa? I’d never in my life eaten an Outspan orange (from South Africa) or a Jaffa orange (from Israel). I’d heard of Australian government officials going to refugee camps in Europe and hand-picking – or should I say eye-picking – those who could immigrate there. Australians in London had exiled themselves, some to avoid the US war in Vietnam, others were writers and artists. Censorship was big in Oz. You couldn’t read D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. You couldn’t buy a book on natural childbirth.

I asked a couple of Australians. “We’re going back”, they said. “Twenty-three years of pain is over!” Gough Whitlam was now the prime minister and the times they were a-changin’.

The Whitlam government had decided that the languages of this land should be written down. The people themselves could then produce books so that everyone could learn to read and write in their own language. But on a stolen, occupied continent with hundreds of languages, there were hardly any linguists. Australians weren’t even aware of the number of languages in the land they lived in. The Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies in Canberra was looking to Canada, the US and Britain to recruit English-speaking linguists. My partner was one, and took the job.

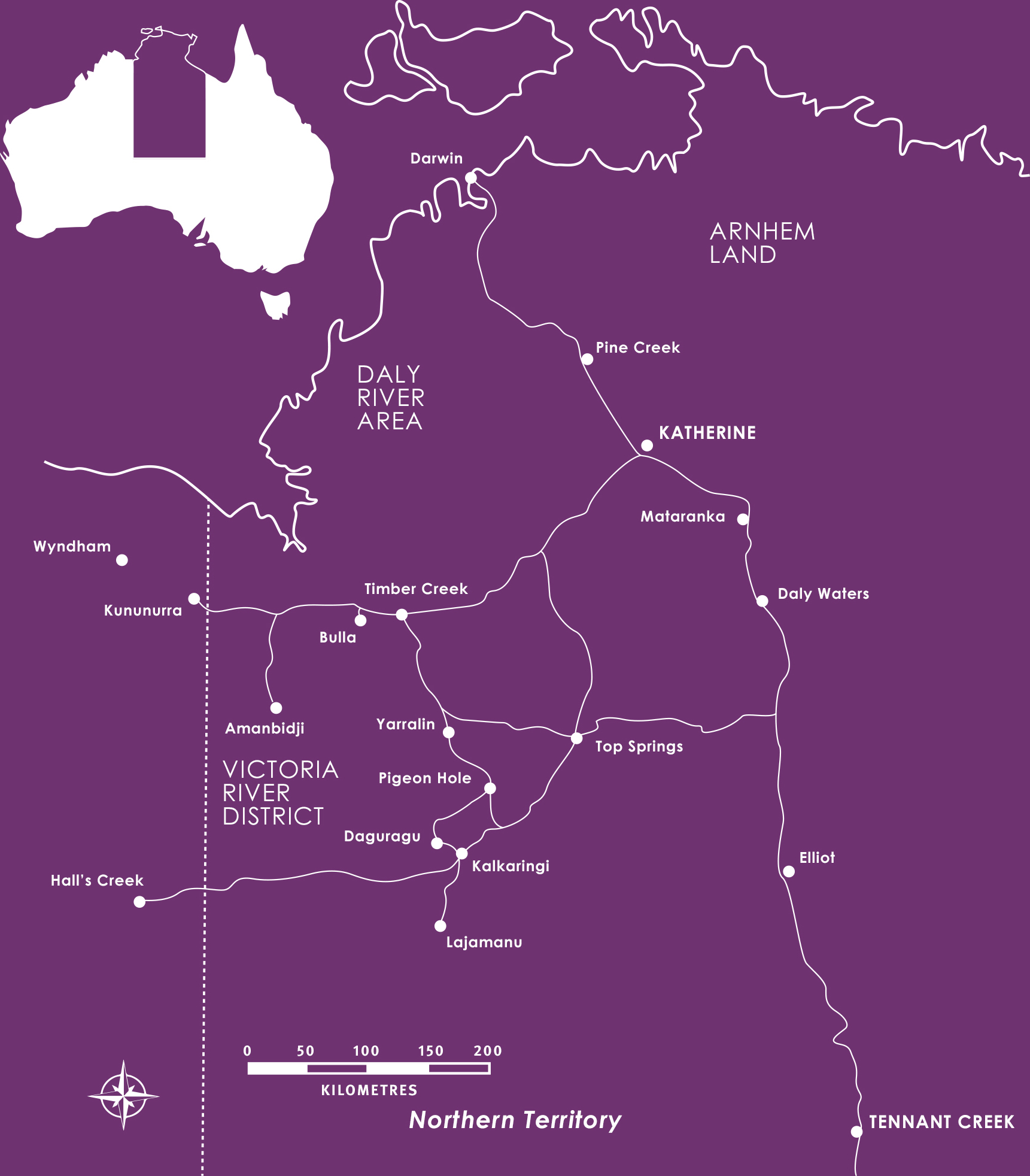

I arrived in Canberra, a strange city, where I went to my first demonstration in Australia. It was at the Tent Embassy, and I got to boo the queen. It was a long way to come to do that! (And I’d done it a few times already!) I was pregnant at the time and was told there was no medical help in the Northern Territory. So I stayed while my partner took off in a Z-plate Toyota. You know what that meant? It meant whoever was in it was federal government. We didn’t know this, but we soon found out. People in the Territory reached for their guns when they saw that number plate, especially in 1974. He was armed only with a pen and notebook, an old-school tape recorder and a map. He’d been given the name of a language, Mudbura, and been told to find it. “Somewhere between Elliott and Katherine, and maybe a bit west of the highway.”

I stayed behind reading the NT News in the library (it wasn’t all about crocodiles then). The headline on the story I was reading just before my partner arrived in Elliott was, “Elliott – Australia’s Little Rock!” They didn’t want Aboriginal kids, who were now refugees from the cattle stations, in their white schools. So they were withdrawing their kids.

An old man in Elliott told my partner that Mudbura people were in the strike camp at Wattie Creek and told him how to get there. He said there had been a strike at the nearby Newcastle Waters station, and they had joined the Gurindji at Daguragu.

Daguragu / Wattie Creek

When my partner arrived, the people met him and politely asked his business. He told them. They said he was to camp on the other side of the creek from the strike village. He was a single white fella, after all, and could be dangerous. “Tomorrow, come over and sit with us and we’ll talk.” An old man and his wife were living on the other side. They kept him company. The old man, called Boogaga, had broken a serious social rule many years before, and he and his wife had been banished. They were old now, so every morning they joined the community – they were both still part of it. But every night they went back over the creek to sleep and live on the other side. My partner, while the talks were going on, did the same. As a result of that, the people called him and Boogaga brothers.

When academics live in communities like this, they often say how they behaved well, they were given relationships, everyone loved them and included them. Maybe that’s a bit of bullshit. A week after my son was born (and about a year after serving drinks to the London meat workers), I was living at Daguragu, in the strike camp, on Vestey’s lease. The first thing I had to do was to learn to live in a society with the most complex social structure I’d ever come across. And I knew of a few: I’d travelled a bit in the world, and even my mob hadn’t always been pitmen, worker slaves to the coal barons of England. But this one! There were 16 categories of human being. The one you got comes from the combination of the ones your mother and father had. And that’s just the beginning.

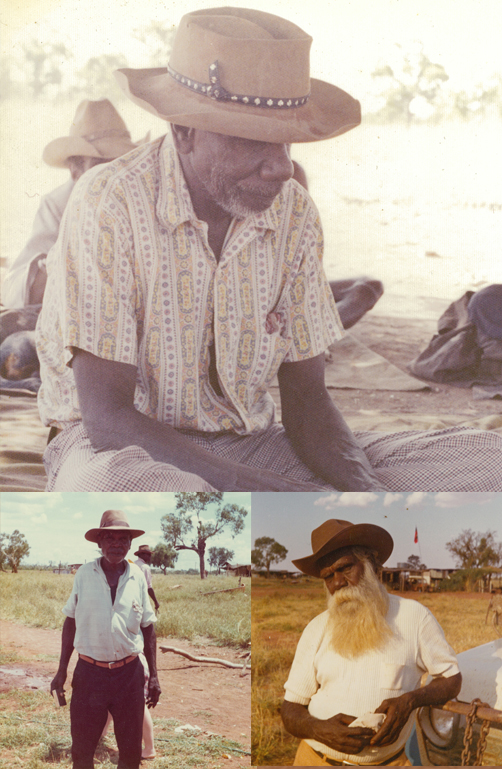

Portraits

VIEW SLIDESHOW

My partner, sitting talking with Boogaga into the evening, could be his brother. So he must be a jampijina, like the old man. Even before I arrived, I was a nangari, and the unborn baby was a jangala or a nangala. And the people hadn’t even met me, didn’t know what kind of person I was! You could be sweet, stupid, clumsy, greedy, big-hearted, an artist, a gardener, a dancer, a cook, a drover, disabled, blind, a bit crazy – it didn’t matter. You were equal with everyone else. You were caught in an amazing network of rights, obligations, care and responsibilities. Some relations were very serious; others could be very cheeky.

The point is, if you had no section to belong to – no social designation – then nobody really knew how talk to you, and you couldn’t learn how to behave. Even the Vestey boss of Wave Hill was given one. I don’t think it meant the people loved him, or that some thought of him as a brother. It meant some people could talk to him. He was around most of the time, ruling their lives, and someone had to make him listen to the demands that were going to come to him.

When I arrived with my week-old son, jangala, we were family now – my partner had a wife and was no longer considered such a threat. So we crossed the creek and lived in the village. They wanted school books and dictionaries, and the linguist had to listen to all the languages, not just Gurindji. He had to listen to Mudbura, Ngarinyman, Ngaliwuru, Nyininy, Bilinarra and more, but we could stay.

Here, too, began my education about Australia – history first-hand from a mob of people who wouldn’t give in. They are known as the Gurindji, but that was so the white fellas wouldn’t get confused. We had a reputation of not being good with lots of languages, different groups and complicated social organisation. We were socially inadequate, you might say. If they’d called it the Bilinarra-Nginin-Gurindji-Ngaliwuru-Mudbura-Malngin strike, it would have confused us simple folk.

Organising the strike

After more than 50 years of massacre, rape, slavery, corporal punishment and misuse of their knowledge, they had planned a strike. And it was a big thing! The demand, at first, was wages. Vestey stations had an annual race meeting and rodeo close to the Western Australian border – the Negri races. Everybody went, including the workers and their families. It was the only time they were allowed to get together from the different stations, not just Vestey’s. It goes without saying they could not have organising meetings at their workplace, even out in the bush. The boss would know they were up to something.

Under cover of the races, in 1962, they’d got together a list of demands for wages, conditions, housing, water and services, and took them back to their station bosses. The next year, they had a report back. Nothing much had been gained. So they did it again – upped the ante a bit. Can you imagine being able to have an organising meeting only once a year? Over this time, they started getting wages, a few dollars. But they never saw them. Their pittance went to the company store. By the time the cost of the rations was taken out, they were told that they were in debt to the company. Living conditions were terrible, huts and dirt floors, so that was it: strike!

Those who walked off Wave Hill in 1966 first sat down in the Victoria River bed. Brian Manning from the Waterside Workers Federation brought supplies. Dexter Daniels, the north Australian Workers’ Union organiser, had been travelling all over the Territory checking wages and living conditions. But the union leadership couldn’t really face the battle if a strike from all the stations had been officially called. In fact, as we knew from Newcastle Waters, workers at other stations had gone out.

When the wet came and the Victoria River flowed, the people moved to a patch of land behind the welfare officer’s house. It was on crown land, kept by the government for a police station, a nurses’ station and the welfare officer. They served everyone on the cattle stations scattered across that bit of the Territory. The government welfare officer at this place actually helped the people. He gave them supplies and material for fencing when they took some land back. He later got the sack – for looking after people’s welfare, I suppose.

At this spot behind the welfare officer’s place, the decision was made to leave the settlement and build a village next to the water hole, Daguragu, on Wattie Creek, on Vestey’s lease, and start the campaign to get the land back. The work of Dexter Daniels and some of the unions had resulted in a few gains already. The Conciliation and Arbitration Commission had been looking at the situation of unpaid, ration-paid and less paid station workers in the lead-up to the ’66 strike. Equal pay was promised in 1965, but became law only in 1968 – to give the station owners time to “adjust”. The words of the man who represented the Cattleman’s Association at the hearing are in the report of the commissioner:

“They did not work in any way understood by us. Discipline and understanding of work is foreign to them. Their society was not competitive in an economic sense. Working for oneself with ambition to achieve some economic goal, was foreign to their society.”

You could take that as a compliment, something to learn from, as I did. But he meant that they could only be slaves, their lives managed. He argued against equal wages. His name? John Kerr, who, as governor-general, sacked Whitlam in 1975.

As the station owners had promised at the hearing, the result of the ruling was that thousands of jobs were lost. Men, women and, yes, children, were sacked. Helicopter mustering was cheaper than using people, they discovered. Families who had worked for decades living on their country were evicted from station property. They were not workers now, but trespassers. As most of the area was covered by pastoral leases, they became refugees on the edges of towns, like Elliott. Some of them had come to the Daguragu strike camp because it was holding on.

Getting an education

When I got there, I’d heard about Daniels and Manning, and how the Waterside Workers Federation and Actors Equity had paid for a speaking tour down south for Dexter, captain major Lupngiari, Vincent Lingiari and Robert Tudawali. (Tudawali starred in the film Jedda alongside Rose Kunoth-Monks. The movie was made by communist film director Charles Chauvel.) Lupngiari told me stories of working alongside Black Americans on the Stuart Highway during the war – they got the same wage as a white soldier. Why then should the people here be getting less than whites?

They had more than 60 meetings down south. A movement grew in solidarity with the Gurindji. It sparked some of the first big land rights marches. I learned about the one in Sydney from Redfern to Vestey’s headquarters, with 47 arrests the first time it happened. I heard about the supermarket action where people walked into Woolies, each choosing a particular checkout. They loaded trolleys with tins of Vestey’s “Hamper” bully beef until there was none left on the shelf. After getting the bill, they suddenly realised the tins came from Lord Vestey’s company, changed their mind, shouted, “Vestey sucks Black blood!” and left the tins piled up at the till. Vestey’s brands were quickly moved off the shelves. The store managers couldn’t have that kind of time wasting.

I learned much from Pincher Nyurrmiarri, one of the greatest political leaders I have ever met, though he never would admit it. I also met Jacob Oberdoo. If a small plane was coming in to see us, it flew over Daguragu and wiggled. That meant we had to go to the landing cleared by the people. Vestey wouldn’t let us use his airstrip. (The Australian media at one time had suggested that the landing had been cleared by the people at Daguragu to allow military planes from China to land and invade the NT!)

Camp Life

VIEW SLIDESHOW

One day, there was a little plane wiggling. The Z-plate went out to meet it. The plane had come from Strelley station in the Pilbara. (This was owned by the people who had gone out on strike in 1946 because of the treatment of workers on sheep stations. It’s an amazing story, told in the book Yandy by Donald Stuart and in the documentary How the West was lost.) Jacob, who travelled with the plane, was one of the many people who had taken on the Western Australian state and the sheep station owners in ’46. The wharfies were in that struggle too, refusing to handle the wool clip, supporting the striking workers. And here was Jacob, flying in from Strelley, bringing food and medical supplies to support the striking cattle station workers in the Territory.

And I met Frank Hardy – he was bringing his documentary to Daguragu for the first time. So there I was, after the meat workers in London, sitting at Daguragu watching The Unlucky Australians with the people who had made it! But even back in 1972, Hardy had been worried. He was wondering about the words of Langston Hughes:

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Looking back, he was right to be concerned. There had been attempts to smash the strikers and to divert them from their demand for the return of land occupied by Vestey. And there was that piece of crown land mentioned earlier. It was about eight kilometres from Daguragu. I think it was called Drover’s Common by the first thieves and became the Wave Hill settlement. When the government saw that the people were not going back to the stations, it decided to build a town on this crown land. The plan was to fill it with striking families and thereby do away with the demand for land rights. The people at Daguragu were asked if they would work on the buildings. Well yes! No strike pay, no dole, why wouldn’t you?! Earn some money!

They built amazing houses. Nothing like them had ever been constructed for people in “remote communities”, as some people call them. There were verandahs, gardens, toilets, bathrooms, fitted kitchens connected to water and electricity. The government said, “Move in – these are for you!” The people said no and took their construction worker wages back to Daguragu. The government then moved in Warlpiri people from what was then called Hooker Creek – Lajamanu. I think the Wave Hill settlement was referred to as “Danglecarrot” for a while. It was eventually called Kalkarinji and gazetted as an open Territory town in 1976.

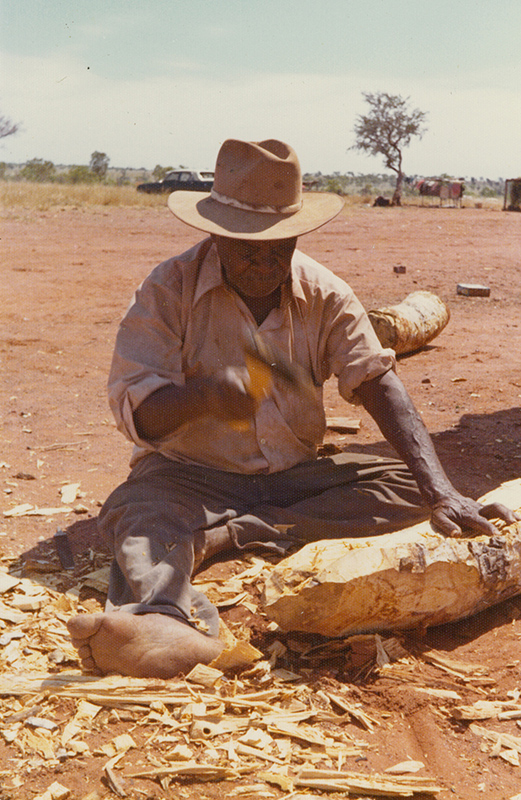

The people at Daguragu had all been fighting for a safe base, that nobody could take again, for people from different groups. They had built an amazing village. There was shelter, a central eating and meeting area, a store, showers, toilets, gardens and cool room. They had drawn up town plans for housing compatible with their social organisation. There were no straight rows – why live in lines? There were plans for a sports ground and a clinic and a school with their own teachers and nurses, maybe their own doctor. They already had a women’s centre. They had attracted the attention, through the student campaigns in the south, of people working on solar power. The place was going to be powered by the sun, and they were going to trial solar-powered motorbikes to get around the bush.

Already on this piece of taken back land, everybody had a job. There were cleaners, gardeners, shop assistants, cooks, bakers, garbos, teachers, musicians, artists, comedians, childcare workers, story tellers, nursing assistants, horse breakers, drovers, ringers, jackaroos, jillaroos, meat workers, butchers, fishers, shooters, mechanics, carpenters, fencers, builders and miners. They were the Muramulla Gurindji Mining Lease and Cattle Station – there just wasn’t a boss. They wanted control of their collective economic relationship with the occupier. They knew they had to have some sort of relationship.

English had been no problem – they had already added it to the four or five other languages they spoke. The stupid press in the south had been surprised – impressed that Lupngiari could crack jokes in English. Peter Nixon from the Department of Aboriginal Affairs had reacted to the people’s demand for their land with the suggestion that they should buy it. Then it would “really” belong to them. A journalist in a press conference during the campaign suggested that option. Lupngiari said maybe the people could pay the cattle station owners a little flour, sugar and tea. After all, that was what they had got for it!

There are so many stories from this time, some funny, some sad. The women had been surprised to see milk dribbling out of my titty. They had never seen that happen with a white woman. They didn’t tell me straight away; they were very polite. And they had fed every white child on every station, so they thought we didn’t have any milk. We laughed together, but the bosses had milked them – literally. After I’d been there a while, they asked me if I knew why some women had only one baby. You can guess what was happening. People were forcibly taken to the hospital, forcibly given anaesthetic, forcibly given Caesareans. Then their tubes were tied. As a result, women were hiding their pregnancies from nurses at the Wave Hill settlement.

There was a time when I was sitting down with Pincher Nyumieri and I discovered that everybody was calling the UK “Big England”. I couldn’t really argue, but I managed a few weeks later to get a map of the world. I showed them England and I showed them Australia. Pincher laughed. From then on it was called “Little England”.

I had work, too. I could read and write English, so I could read letters and take down what people wanted to send. I could add numbers, so I could work with the young women so they could run the store themselves. They taught me to fish, so I could contribute to the fresh food supply. I could work with the health worker doing colour codes for names, medicine and doses.

It was an amazing place.

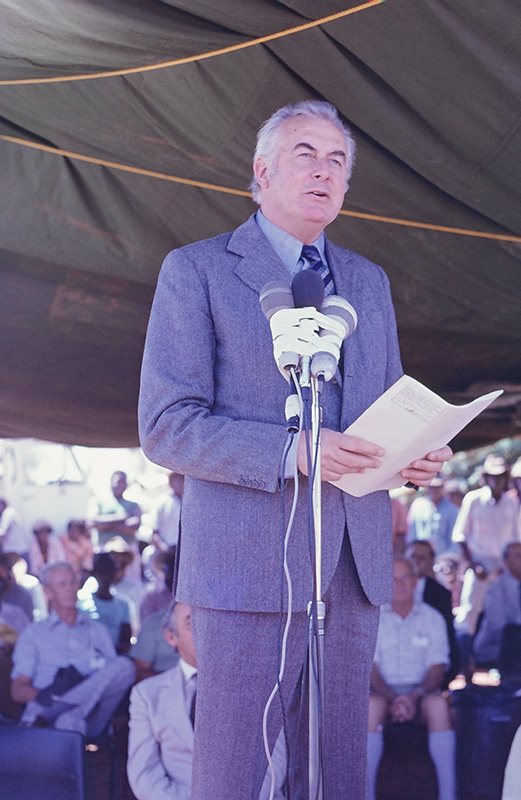

Dream deferred

Then came August 1975. The land was going to be given back in an amazing ceremony by Gough Whitlam, the prime minister. It was going to be a big event! Just a couple of days before, workers arrived to dig pit toilets. We got two blocks of them. The visitors had to be cared for, after all. Workers came to put up the bronze commemoration plate on a big rock planted into the ground. When they asked where they could plug in their drills, they were shocked to find we had no power supply. There was an emergency call for a generator.

The day dawned and the planes flew in, full of “important” people. After everyone ate Vestey’s beef from the barbecue, the company representative got up and handed 1,250 sq miles, on paper, from the thousands Vestey had, back to the government. Then Gough performed the famous act. It was very dramatic – the land coming back to Vincent. But the dirt he was dribbling into Lingiari’s hand was only a 30-year pastoral lease. It wasn’t, “You’ve got your land back forever” – after all, this was before the land rights bill became law. The area was now empty of cattle. Vestey had paid helicopter shooters to finish clearing the land. Then the Vestey boss “generously” promised 400 head of cattle as a gift. (Vestey got off cheap this time. In December 1972, his top manager in Argentina, Ronald Grove, had been kidnapped by an armed group, a Trotskyist one I think. They asked the cattle baron for a million dollars. And they got it within two weeks. So 400 bullocks? – phuh!)

1975

VIEW SLIDESHOW

The dignitaries left before sunset. We had a great night under the stars, listening to music, singing, dancing and telling stories. The next day, workers came early, took down the toilets and filled in the pits – we didn’t even inherit the new dunnies.

Frank Hardy’s fears were being confirmed. Even before I left Daguragu in 1977, the government had imposed a white station manager from a South Australian pastoral consultancy. I think only three men were paid as station workers, and the number one stockman, respected by everyone, wasn’t one of them. I remember one time the white manager tipped and bogged a small grader on the bank of the waterhole. He tried to get it out but couldn’t. He called in the paid workers. That took a while because they were out fixing fences. But all three were working on it now with quite a crowd, kids laughing and playing, along the opposite bank. They let it go on for a while, then people stood up, crossed the creek, cut bark, cut branches, working together. Twenty minutes later, the white manager was driving off on his machine and everyone was laughing! We laughed, but we were angry. Why can’t we all be useful all the time? I was angry, thinking of a dream deferred.

In the years that followed, the Muramulla Gurindji cattle company was accused by the Cattleman’s Association of harbouring tuberculosis and brucellosis in their new company-branded cattle. They had to build a very expensive fence around their 1,250 sq miles and shoot their cattle.

We had sat around the radio in November 1975, listening to the news from Melbourne on Radio Australia. John Kerr kicked Gough out. Masses were on the street and the army was put on alert. What was happening? Some were sure that the coup was a reaction to Gough handing back the land – everyone knew Kerr’s history.

Whitlam’s successor, Liberal prime minister Malcolm Fraser, passed the Land Rights Act in 1976. But now it applied only to the Northern Territory, and crucial parts were deleted. And the people had to go in front of the land commissioner and prove their ownership to the capitalist legal system. Even then, only those first people defined in Australian law as “traditional owners” could claim the title – with the help of anthropologists, of course! The land Vincent Lingiari was responsible for wasn’t on the 30-year pastoral lease. I think it was in Western Australia, across a colonial border. But then, he hadn’t been fighting for himself.

It was 1986 before the strikers got inalienable freehold title “in perpetuity”, and they were in trouble. Inalienable freehold title to land means you can’t buy or sell it. Fair enough, but in the capitalist system, that means the land is worthless. And if it is worth nothing, then you can’t use it as collateral to get a loan from a bank to start anything. That’s why it ended up leased to a white grazier.

No justice – just us!

The invasion continues. Since 1788, it’s been about all the same things: theft of land, theft of children, theft of labour, theft of language and the smashing of people’s social organisation. Everything was done on the assumption that the people were inadequate, incapable of making decisions, incapable of looking after themselves – a blatant, cruel lie. And it continues today. Kooris, Murris, Nanga, Nungar, Yulgnu, Ngumpin – these words all mean human being in the languages that they come from. Human beings all over this country are still having their kids, their work, their land and their very lives stolen.

In 2007, the invasion of the NT was, as it was in 1788, legalised and intensified. It was called “the intervention” and involved soldiers on the ground in some places. For the first time in history, a government official set up an office at Daguragu. It’s gone now, but it was a demountable surrounded by a high fence. She used to drive in, lock the gate and go inside. At the end of the day, she’d drive out, lock up and leave. She never spoke to anyone and nobody spoke to her. The people didn’t even know her name.

At the end of 2011, police drove into Daguragu and kept mothers and grandmothers away while welfare authorities took a little boy. Months later, we found out it was because he was “malnourished”. Doesn’t that mean he needed good food? Try buying enough to eat at the store on a “basics card” – a ration card. Even milk costs around $5 a litre! The child removals happen all over, but this was the first time at Daguragu since the village was established by the strikers and the land was won. Women, mothers and grandmothers, trying to block the car carrying the child, were pulled and held by police.

And we’ve seen the battles, not only Kulaluk in Darwin, but at the town camps in Alice Springs. These were all gained during the land rights legislation time. Redfern has to fight again for Redfern. We now know from the remote – “remote”? – places where people live in Western Australia that they’re pulling down houses and smashing them and forcing people off their country, saying they have to live on the edges of a town. And, of course, we all know what’s happening with resources and mining companies.

2011/2016

VIEW SLIDESHOW

The struggle continues. Workers have organised against the ration card. People have rallied all over the country against forced community closures, deaths in police and prison custody, the torture of children inside Don Dale prison, the exploitation by mining companies and the forced removal of children from families and communities. The demand for a treaty on land never ceded is growing stronger.

The anniversary of the cattle station workers’ strike and walk-off at Vestey’s Wave Hill station is called “Freedom Day”. The celebration happens mostly at Kalkarinji – Wave Hill settlement, “Danglecarrot”. Politicians and government officials who are responsible for the smashing of communities attend it, celebrating “freedom”. On that day in 2011, the people carried banners protesting the intervention. In 2016, the banner and T-shirts said, “No justice, just us”, and people turned their backs and stood in silent protest when the minister for indigenous affairs, Nigel Scullion, spoke. Meanwhile, the “basics” ration card system is rolling out for everyone, as did the work for the dole system.

The strike village at Daguragu in the ’70s was an amazing place to live. People took control of their own lives. Everyone looked after each other, no-one went hungry. If we learnt anything from that time, it’s that we have to do it again – and again and again. As for self-determination, it’s no “white man’s dreaming imposed on black people”, as someone once said. It’s everyone’s aim, it’s our plan! The mining companies and the big businessmen and government people better watch out. We all want to get together, look after each other, work for each other, educate each other, control our own affairs and look after the planet.

Self-determination is what I want, and it’s obvious I won’t get it until everybody gets it. And if they get away with what they are doing to the people in this country, there will be no justice or equality for any of us. People like me are not helping the downtrodden – I’m not. I fight alongside the people who are fighting. I fight alongside them because if they lose, I lose, and when they win, I win – I am selfish. And like the men in the pub in London – “One Struggle, One Fight!” – we are all brothers and sisters.